At its heart, drawing is simply making marks. Before we think about subject, style, or meaning, a drawing is just marks on a surface. Each mark has its own character, shaped by the artist’s hand, the tool, the pressure, and the intention. In this way, every mark is like a signature: unique, unrepeatable, and showing the artist’s state of mind at that moment.

Like spoken language, drawing communicates through changes in pressure and weight. A firm line feels different from a light one. These differences guide the viewer’s eye and affect how we see the form. Heavy lines can show strength or confidence, while lighter marks can suggest delicacy or movement. Without these changes, a drawing can feel flat and lose its expressiveness.

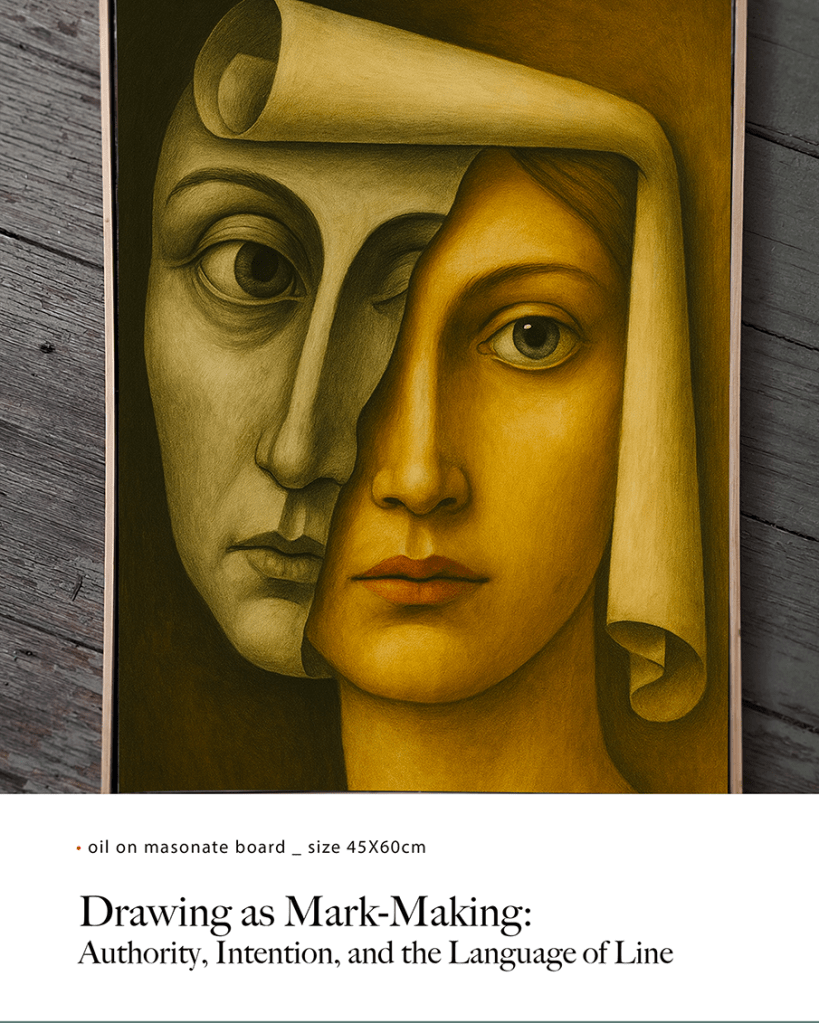

Lines of consistent thickness outlining a figure or object often flatten the image. If you outline a figure or object with lines that are all the same thickness, the image can look flat. When every edge seems the same, you lose depth and a sense of space. The drawing becomes more decorative than three-dimensional. But if a line changes thickness, breaks, or fades, it brings the drawing to life. These lines help curves flow, edges feel open, and forms turn in space. Even a broken or fading line can be powerful, hinting at movement, light, or change without being too obvious. Mark will always read as such. The viewer senses uncertainty immediately, regardless of the subject being drawn. This does not mean every line must be bold or aggressive, but it must be intentional. Even the softest, quietest line should be placed with clarity of purpose. Authority in drawing does not come from force, but from decisiveness.

This is where discipline enters the practice of drawing. Every mark should serve a reason—defining a form, suggesting weight, directing the eye. This is where discipline matters in drawing. Every mark should have a reason, like showing a shape, suggesting weight, guiding the eye, or expressing a feeling. Marks made out of habit or uncertainty can quickly clutter the drawing and weaken its effect. Knowing when not to draw is just as important as knowing where to put a line. to engage, to complete what is implied rather than explicitly stated. In this restraint, drawing becomes less about describing everything and more about choosing what matters.

In the end, drawing is a language made of marks. Like any language, it takes awareness, intention, and practice. When each line has confidence and purpose, the drawing speaks clearly, without extra details or doubt, and with a voice that is truly its own.

Leave a comment